may 2013 - feb 2013

May 31st

Boycott Poster 1

Boycott Poster 2

May 27th

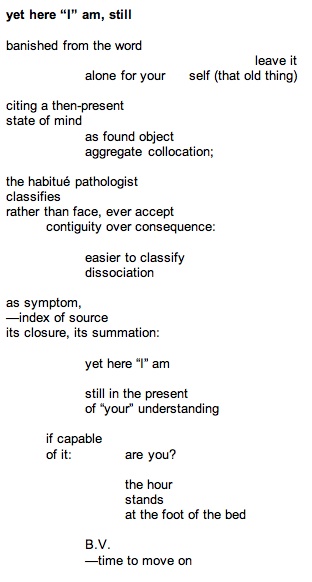

A letter to my publisher recently concluded a paragraph with the following which continued to have me thinking:

God how comfy the armchairs of identity beckon to some especially as they grow old and tired of walking. My walking is not done ha ha

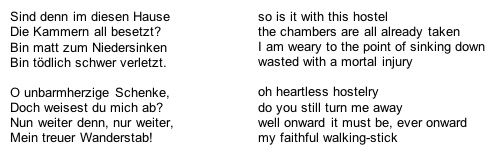

It reminds me of years ago when my father had a stroke and was taken into hospital where he never spoke again but lay for a number of weeks before he died. We visited talking to him nightly just in the hope that he could understand, as I think he did. It was in January and a miserable experience getting the bus out each night and back often it seemed in the rain. When I came home I sometimes would sit on my own for a while and seemed to find some kind of comfort in Richard Tauber’s great 1927 recording of Schubert’s Die Winterreise. The recording has Tauber singing 12 of the 24 songs, the one which then seemed to carry the most resonance being “Das Wirthaus” in which the solitary traveller comes to a graveyard and hopes for some accommodation there, but there too all the accommodation is already taken. The last two of the four verses are thus:

A slightly restricted transfer of Tauber singing “Das Wirthaus” can be heard on YouTube here

May 26th

May 23rd

Not just to change the nature of the debate, but to change the nature of the space it inhabits. Absolutely not to accept the contours of the space provided.

Some will understand the meaning in politics. Harder, much harder, to understand the meaning in writing.

May 22nd

Mallorca.

May 17th

I have updated the links page bringing the Etruscan Books link up to date here. Nicholas Johnson's primary work from conception to completed article of my last four books is perhaps not recognised and I think it ought to be, without him the books simply wouldn't be there; the details of his solitary toils to get them to fruition from a life that is neither cushy nor moneyed is another matter for another day. Just another story from the smallpress progressive poetry history. An excellent solitary publisher with whom I am very happy to be associated in my work and personal life.

May 16th

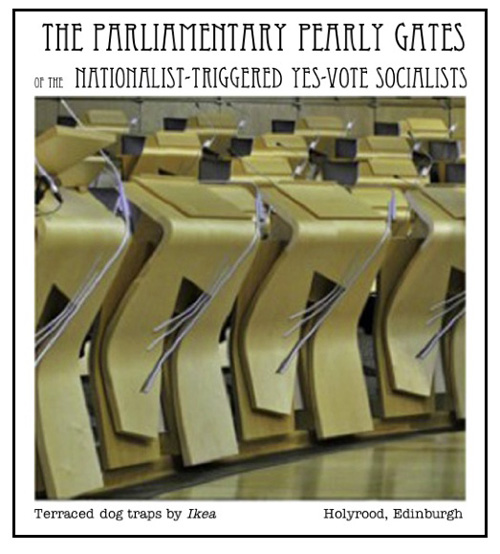

I am sorry to report that the terminal boredom I have been suffering from regarding the so-called “independence debate” has now reached critical proportions. As I mentioned at my booklaunch on Friday last it almost surprised me I was still alive six months after terminal boredom had set in.

Remedy is abstention. I intend to avoid on the subject all radio and television programmes, conferences and their reports, studio debates, published statements of personal position, newspaper articles and comment columns to the power a thousand, minceheads from Westminster droning on about “the union”, yes-vote persons endlessly and cavalierly describing those not on their side as “unionists”.

I am interested in politics, that I know. In fact, I think that is actually the problem with my boredom. I don’t expect many of the above to understand that.

May 11th

Definite Articles is now on sale from my website homepage. Price including postage (which with its weight and the new UK postage rates comes to £3) is £15 total, with extra itemised for EU or rest of world sales.

May 2nd

May 1st

I will be reading from and launching Definite Articles on Friday May 10th at 7.30pm at the CCA in Sauchiehall St in Glasgow. Admission free.

April 26th

If you think you’re not getting enough news about Scotland of actual significance from its newspapers or electronic media, maybe you’re not casting your newsnet wide enough. Nato is so central to the foreign policy heart of Labour, Tory, LibDem and SNP party members, you would think they would be boasting about Nato’s training exercise “Joint Warrior” that’s been taking place in Scottish waters this past week. After all it’s been the biggest exercise in the twice-yearly series to date with 40 warships, 40 fixed wing aircraft, 30 helicopters, and no less than 12,000 military personnel taking part in such as mock landings on hostile bits of ehm, Carnoustie.

All this for the “Response Force Task Group” which can be sent at short notice bombing and fighting anywhere in the world when it gets the nod. So that’s all right. Nothing there that will be affected by the referendum. Thanks Alex.

And where can you read about it? In the Portsmouthnewspaper the News. Here.

April 23rd

In a talk I gave two years ago on R D Laing and Beckett at the Mitchell Library in Glasgow, I came to the conclusion that whilst Laing’s The Divided Self of 1960 was one of the great books of the twentieth century, his The Politics of Experience seven years later was one of the most irresponsible. The Divided Self had laid bare the nature of microstructural complicity by which two persons in power can form the given sides of a relationship triangle functioning to deny full personhood to a subject colonised third. The Politics of Experience on the other hand almost certainly caused sundry personal tragedies through its implicit romanticisation of psychosis as rebirthing authentic inner journey that could take place in an outwardly insane society. The psychologically vulnerable reading the book were in a very dangerous space.

Laing left the army in 1953 and took up his first job in Gartnavel Royal psychiatric hospital in Glasgow. A book he is likely to have been made aware of at the time had been republished six years earlier in 1947:The Philosophy of Insanity, by a Late Inmate of the Glasgow Royal Asylum for Lunatics at Gartnavel. The book itself dated its first publication from the late 1850’s, and contained an account from 1843 of a psychotic breakdown which I have to say I find contains more honest sanity of overall outlook—where sanity = health — than Laing’s 1967 publication.

I purpose to note down a few of my recollections concerning my thoughts and actions while under the influence of the disease, in the hope that they may be useful to those whose business it is to watch over the insane, and a warning to those who through ignorance or recklessness abuse their minds till the tortured spirit, like a fire-begirt scorpion, turns upon itself and stings.

One night, after a number of weeks of fearful suffering, as I was lying in bed tossing, sleepless and despairing, a most horrible impulse seized upon me, an impulse impelling me to destroy one who of all living beings, most deserved my love. I buried myself under the bedclothes and struggled with the hellish impulse till the bed shook. It still gained strength. I sprang up, clung to the bedpost and sank my teeth, in the agony of despair, into the hard wood. It was uncontrollable. I shut my eyes, bowed down my head for fear that I should see her, and rushed out of the house. Barefooted, with no covering save a nightshirt, I ran through the streets to the Police Station and implored them to lock me up. Fortunately the officer on duty was a humane and sensible man. He gave me a watch-coat to wrap around me, kept me under his own eye, and, I suppose, sent notice to my friends, for my wife and sister came with clothing. The paroxysm had passed, and, gasping, panting for death in any form, I accompanied them home, steeped to the lips in despair.

I had a little sickly boy, a special favourite on account of his helplessness; and after I was removed to the Asylum, night and day the weeping and wailing of that child rang around me, and the cry, “I’m hungry, father, I’m hungry,” scorched my heart like fire. This, to me, soul-harrowing cry broke down what little reason I had remaining; and when my wife came to see me, I insisted on taking my clothes off to give her to sell for food for the children. I inquired wildly for that child; she told me he was at home and well. How could I believe her, when I heard him distinctly while she spoke, sobbing and crying, “I’m hungry, father, I’m hungry.” I became convinced that the child was in the Asylum, although I could not see him; and I was in the constant practice of putting a portion of my food at every meal into a corner, in the hope that he might fall in with it in his wanderings. His voice became weaker; and then the wail changed to— “My father does not care for me now.” The whole of my food was laid into corners for him now— I could not taste it. This was allowed to go on until it was evident that it would end in death, and then I was shut up in a room by myself, and food of the most savoury description offered me and left with me. I tried to take it, when — “I’m hungry, father, I’m hungry,” from that now weak, dying infant voice, again pierced through my soul. I felt the blood rushing to my head —flames seemed to issue from my eyes, and then comes a blank in memory’s book, the only blank that in all my sufferings I have ever known.

I have reason to think that about a fortnight elapsed before memory awoke from that death-like slumber. How I behaved during that time I never knew; but the first thing I remember was awakening as out of a horrible dream. I think they had been trying what cold and darkness would do for me, for I was chilled to the marrow, and the place was dark. I thought to myself, without speaking, how long have I been here, when instantly a voice within me replied, “a thousand years.” Impossible; I could not live so long, I thought, when the voice again replied, “thou shalt never die.” The idea of never dying struck more terror to my soul than ever the sentence of death did to the veriest coward that ever crawled and crouched and begged to live. I thought I saw a chink in the wall through which light was streaming. It was imagination, for it must have been a solid wall. I looked through it, and there was a paved court with stables all round and troop horses tied to rings in the wall. Some soldier-like men were grooming them, while others were cleaning carabines, holster pistols, and swords. I knew now, what I had before suspected, that the Asylum was a barrack for banditti—the pretended patients a brand of brigands, and that there was not an insane or an honest man in the establishment. This idea continued for a long time in full force, and I had not got rid of it when I left the Asylum. It received rather a startling confirmation the first day, I think it was, after I was brought down from seclusion. They were at that time furnishing the west house, and two or three carts of furniture were driven past the window of the gallery in which I was placed. I recognised this at once as plunder and could distinctly see a number of valuable articles belonging to a friend of mine who resided at no great distance from the Asylum.

To many a day of agony did that delusion doom me, for I was in terror for the fate of any friend who came to inquire for or to visit me; and the very communicative spirit which had now taken permanent lodgings within me assured me that if I gave my wife or any other friend the slightest hint about the character of the place, they would never be permitted to leave the Asylum alive. Had it not been for this, I would have positively prohibited my wife from visiting me, although I knew that by so doing I would have opened the floodgates of utter despair. These visits were the “be all and end all” of my existence; and perhaps, assisted by the agony thus mingled with them, kept my spirit alive and saved it from sinking into that death of the intellect, idiocy. Many a dark hint I gave her; and one time after she left me the idea that I had spoken too plainly and that they had killed her in consequence, roused me into madness again. What a fearful week of sleepless suffering. Could I have got at that magazine of gunpowder which I believed these robbers had stowed away in the cellars under the Asylum, how eagerly would I have applied the match which would have blown us all to destruction. My wife, however, came on the appointed day as usual, and brought the child with her, whose hunger-stricken cry had so tortured me. He had been in the country and had greatly improved in health and appearance; and as the little fellow clung round my neck and kissed me, I could not help thinking that he could not have been quite so hungry as he had said. It would appear that nothing short of the utter destruction of itself can satisfy the insane mind; for they had not long left till I fancied that the child was still in the Asylum, and that he had been fattened up by some infernal process for the purpose of deceiving me and that his mother had been compelled to join in the conspiracy against her child and me.

I often could not get sleep, nor even get attempting to try to sleep, for that spirit which had taken up lodgings in my stomach, replying to every thought and most pertinaciously insisting that I should listen while it read to me out of a book, the words of which alternately fell cold as haildrops on my brain or flowed upon it like a stream of molten fire. Strange to say, circumstances which could only have been seen or known by me in infancy, and of which I was entirely ignorant but which, by after inquiry, I found to be true, were mingled with the most horrible lies. The truths must have lain forgotten and illegible in some dark corner of the brain till lighted up and rendered readable by the wild glare which madness throws on everything around. Stung to the quick by a fearful lie which he was reading about my father, I demanded the name of the book. “It is the text-book of hell, the bible of the damned,” was the instant reply. After this, let him do as he liked, I would listen no more to him or his book; and by perservering in this, the entire delusion slowly faded away.

During the whole period of my residence in the Asylum, my wife visited me upon a stated day each week; and except at the time of my seclusion, when she told me that I was too ill to be seen, no week passed without her seeing me. During a portion of the time she had to travel from Rutherglen seven miles distant from the Asylum. There was no conveyance between these places those days; yet, let the day be ever so stormy, there she was, true as the sun to her time. To this, to her I owe my preservation from suicide or idiocy. These visits gave me something to think upon, they were, as it were, a solid spot in a troubled ocean whereon the spirit could occasionally rest. Often when I felt mad feeling arising or a cold icy feeling of stupor creeping over my brain, I have been soothed or roused by the thought of seeing her and hearing from my children, my love for whom madness had only inflamed. Before the close of my confinement I believed that all my children were in the Asylum, and I heard their different voices under the floor, screaming to me to save them from tortures which I dare not name. It would have required a brain of brass to have withstood this; mine was never composed of any such material, and I would stand motionless as a statue for hours, feeling little, thinking little, and only possessed by a dreamy consciousness that I existed; and then a cry of agony from some much-loved voice would ring through my brain like the last trumpet sounding the resurrection, then instantly that corpse-like form was raging with mad life and that dark mental sepulchre was gleaming bright with fires that glowed like hell.

My wife saw that recovery was getting more hopeless— that I was getting absent and stupid; in plain terms, that I was sinking into idiocy, and she at once determined to try to save me, let the consequences be what they would. In the face of the earnest remonstrance of the physician belonging at that time to the Establishment—who had a bad opinion of my case from the first—who assured her that I was dangerous, and the advice, almost the threatenings of relations, she took me home, not in ignorance nor recklessness, for she knew that there was danger and was calmly prepared to meet it. She told me since that she never expected I would be much use in providing for the family; but that she intended me, when I was a little more settled, to take care of the house and children while she wrought at a business which she followed before our marriage for our support.

Although very unsettled for some weeks, so much so that any one possessed of less love or firmness than her would assuredly have sent me back to the Asylum, the change and the society of my family saved me; and although for a considerable time not quite fitted for the duties of the situation, a true friend, a cousin of my own, gave me employment, and instead of finding fault with my shortcomings encouraged me to perservere; and thus although I have always been willing to act as nurse to her babies, she never yet has been required to work for their support; nor has she ever rued the day on which she took her poor insane husband by the hand and walked off with him from among the doctors who, I have no doubt, thought her own sanity a little doubtful.

This subject is to me decidedly painful, but I do hope that my treatment of it may be a means of encouraging friends to persevere in their attention to relatives who are thus afflicted; and in this hope I have told my plain truthful story, and who knows but that it may soften the prejudices which almost everyone entertains against such as I; and I may add, for the consolation of the afflicted and their friends, that a fit of insanity does not necessarily permanently injure either the feelings or the intelligence of the person, after the fit has passed. For myself, I can truly say that my entire mind was clearer and stronger—my conduct more rational, and my imagination, naturally very strong, more under control after my recovery than it had ever been during any former period of my existence. Still, I suspect that grief or disappointment, irregularity of living, especially want of sleep, may have a greater tendency to induce mental derangement in such than if they had never been thus afflicted. This is merely a supposition, but that they belong to the nervous class subject to this disease is a certainty; and as they thus carry one part of the disease within them, they should be doubly careful to avoid all things tending to produce unhealthy mental excitement which, in their case, is all that is wanting to produce another attack.

April 15th

April 13th

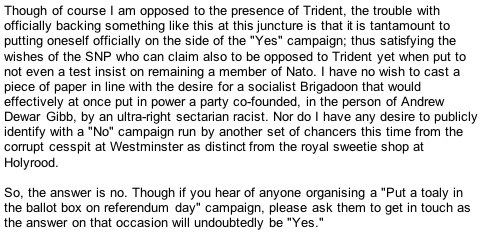

There is a Scrap Trident demo taking place in Glasgow today and I was sounded out about making a contribution to it on the behalf of the organisers, CND and the Radical Independence Campaign. They were looking for “Scottish cultural figures to make statements in support of the demo and possibly speak at the rally”.

I replied thus:-

The last paragaraph was meant as ironic. I have no more desire to get involved in organised ballot-spoiling than ballot-choosing.

April 12th

It’s one thing to have a nationalist movement against a foreign power using an army of occupation, as was the case in sundry British colonies. But the only army of occupation in Scotland consists of Scottish soldiers home on leave from Afghanistan. The economic and political stratum members of which sold Scottish sovereignty three hundred years ago will remain as firmly ensconced after any poll on “independence”, no matter what the result. So much for the “give us back our country” cry. Who is the “us”, who is the “we”?

Which means, who and which is the “self” when the 2014 referendum issue is guised as an issue of “self determination”, as if this was a more authentic and fundamental alternative to mere “nationalism”. It isn’t, and it can’t be so long as the "self" is undefined. If it is to say it is “the self of the country”, “the people” as to say “the Scottish people” etc., then we have to define what we mean by Scottish; which goes straight to the prescriptive versus descriptive mode, which in the nationalist binary comes out as “pure Scots” versus what Sturgeon when challenged calls “inclusive civic nationalism.” Because when one actually examines the “self determination” mode via the proposed Scottish referendum on independence, it is nationalism, be it prescriptive or descriptive, that comes out top in the wash.

If it is from within the context of the referendum one is speaking, the proposal that it is about self-determination not nationalism is delusion; one gladly pumped by nationalists seeking the active help of many who would not want to be defined as nationalists: who might distrust it for many reasons, not least its predilection to racism. Self determination, even “independence” can be a respectable ideal. But for me it must involve a different type of "self", and a different type of "independence", than that which this nationalist-sponsored and initiated Scottish referendum has to offer.

April 9th

April 3rd

March 23rd

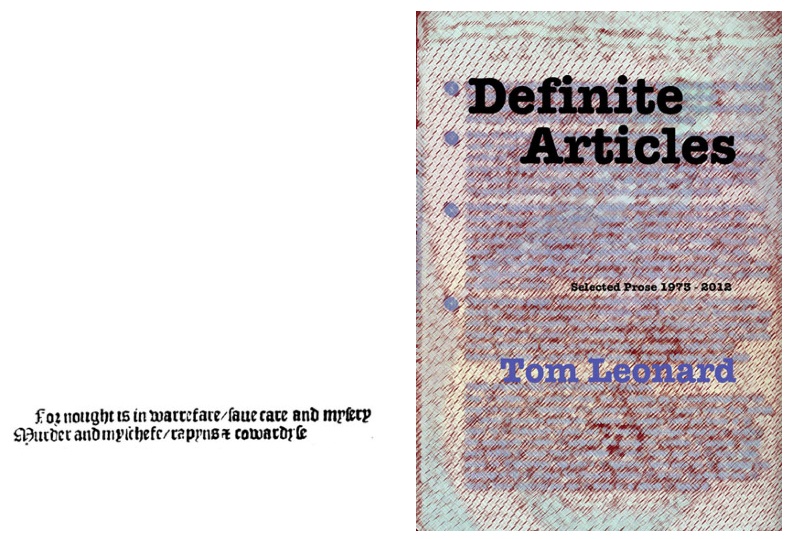

Publication of Definite Articles is moving on after illness with my publisher at Etruscan slowed things a bit. The book should now be out around the end of April.

Above shows the front cover on the right, with on the left the words that will appear on the back. The scanned two lines are from the 1530 publication of Alexander Barclay’s Eclogues: For nought is in warfare save care and misery, murder and mischief, rapines and cowardice.

March 18th

Life goes on.

March 11th

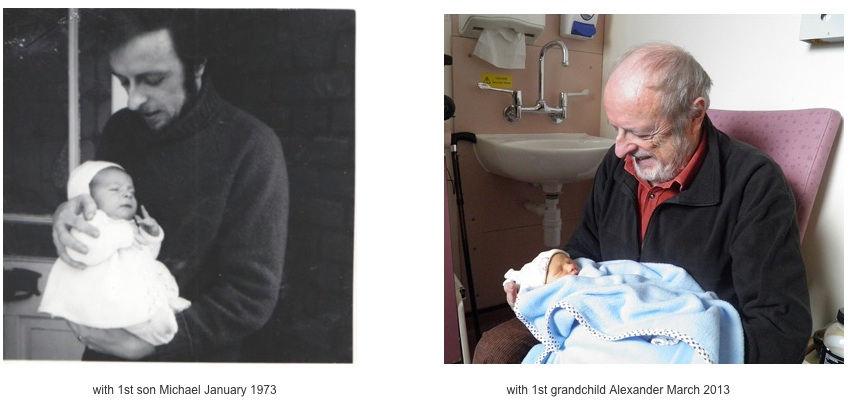

Kingston-upon-Thames. Our first grandchild.

This little fellow arrived at a minute past eleven this morning. His parents Lucy and Stephen have named him Alexander and intend calling him Alex.

March 3rd

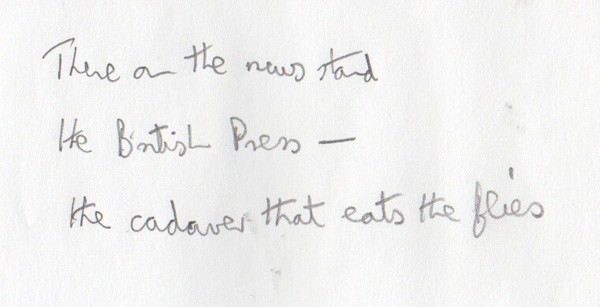

Meanwhile back at the sweetie shop.

March 1st

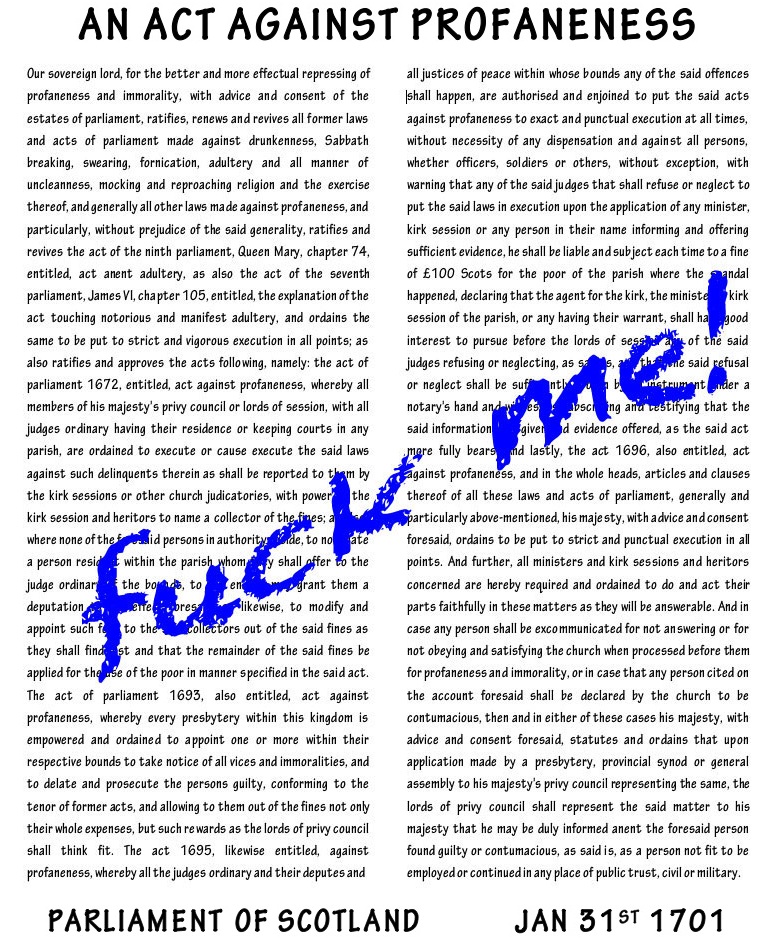

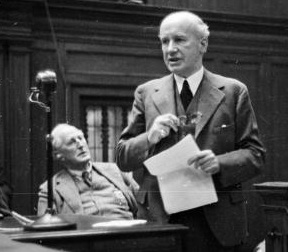

HISTORIC SECTARIAN CLASS RACISM IN SCOTTISH NATIONALISM

The Case of Professor Gibb

[Andrew Dewar Gibb: Co-founder of the Scottish National Party 1934; Leader of the Scottish National Party 1936-1940;Chairman of the Saltire Society 1955-57; Professor of Scots Law University of Glasgow 1934-1958]

Andrew Dewar Gibb at the Scottish National Conference 1950

Excerpts from Gibb's three books on Scottish Nationalism

February 22nd

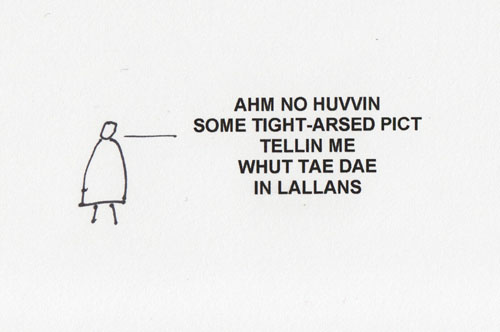

The Lallans movement is the linguistic eugenics arm of nationalism.

February 21st![]()

![]()

February 10th

From a notebook: Clare not a social poet like Burns. What I have loved in Clare is the tenderness of an isolated individual being with an observed part of nature, and letting one as a reader be with him in the observing. Burns is never an isolated figure in this sense, but always part of a social structure: even the ploughman turning up the mouse’s nest is at work, part of the social structure of employment and exchange. Clare on the other hand lies about in the fields and woods, he is not in any employment, never “going about his business”. Burns does not shape an interior monologue which he hands over to be the interior monologue of the reader. Clare does this, to an extent at any rate: one becomes an isolated reader reading Clare, one’s separateness is a given. Not so with Burns.

For Clare then in a way there is a kind of social structure between writer and reader. In Burns the social structure is already in place beyond the page, and he is part of it. You are too, or you aren’t.